The Road to Safe Self-driving

Optical flow prediction systems in autonomous cars.

01 December 2019 Anurag Ranjan 5 minute read

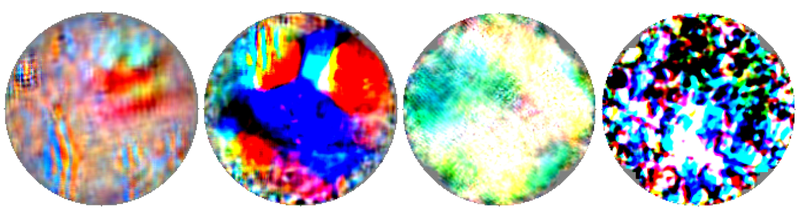

A simple color patch could severely affect the optical flow prediction systems in autonomous cars

These patches could become safety hazards for self-driving cars. Reproduced from Attacking Optical Flow.

Self-driving has been a long-awaited dream for so many of us in artificial intelligence. About 30 years ago, Dickmanns and Zapp integrated several classical computer vision algorithms in a system that would drive their car automatically on a highway. Today, this is easy to do. The tricky part is the problem of generalization. Can the self-driving car work on all roads, or under all the conditions? Today, the answer to this question seems to be - deep learning. Deep neural networks are believed to be the most generalizable models so far. The idea, here, is to use lots and lots of data and train neural networks that learn to solve self-driving. However, deep neural networks seem to have a problem. The problem of being sensitive to adversarial attacks.

VaMoRs - The experimental vehicle for autonomous mobility and computer vision. Reproduced from Dickmanns and Zapp, Autonomous High Speed Road Vehicle Guidance by Computer Vision.

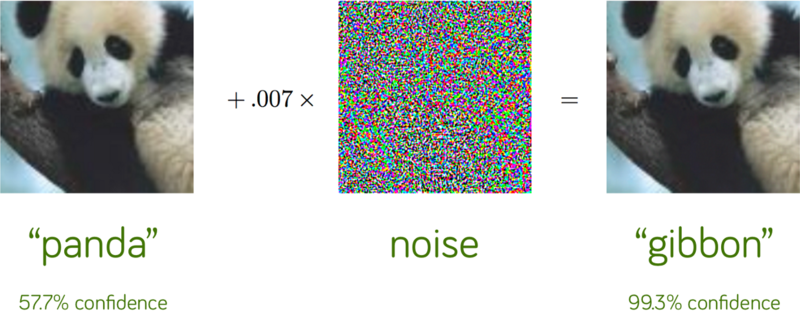

The first concern was raised by Nguyen et al. when they showed that adding small noise to an image could completely change the predictions of neural nets. However, it is not very practical to construct a scene such that the image captured by the camera has this noise pattern. This means that even though the neural networks have this problem, it would not be a practical concern.

Reproduced from Goodfellow et al, Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples.

This idea was soon challenged by Evtimov et al. By placing some stickers on a stop sign, they could confuse the system to think that it was a 50km/h speed sign. However, this needed careful construction of the speed sign, and the access to the car’s systems. In December of 2017, Brown et al. would create a universal patch that could successfully attack several image classification networks, even those that were not accessible for synthesizing an attack patch. The patch here was of a significant size - one could notice it in the image.

Now, for the first time, we target the optical flow networks. Self-driving cars use optical flow networks to estimate the motion of objects on the road. This is later used for making decisions to control the car. Attacking optical flow networks means that the estimated motion of objects could be completely wrong. It could mean that a car moving at 10km/h towards the system is seen as a car moving at 100km/h away from the driver. This would be a serious concern. This is exactly what happens to state-of-the-art optical flow networks. Furthermore, in this case, the patch is really small - about 1% of the image size.

FlowNet2 with and without the patch attack

How does it happen?

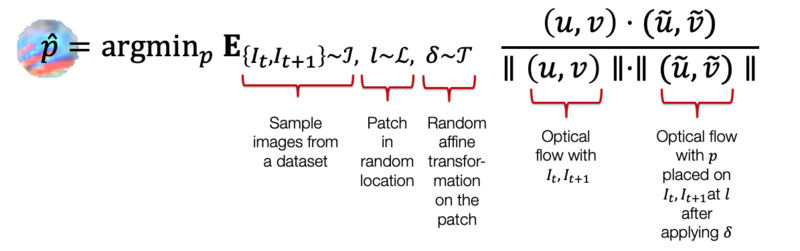

We synthesize these patches by optimizing over the optical flow networks. We optimize for patches such that the direction of motion is reversed when the patch is applied to the image. Furthermore, we randomly augment the patches at different scales and rotations of the patch during the optimization steps. This is done so that these patches can robustly attack optical flow networks at different scales and orientations of the patch. Formally, the following expectation is minimized to obtain the patch.

Why does this happen?

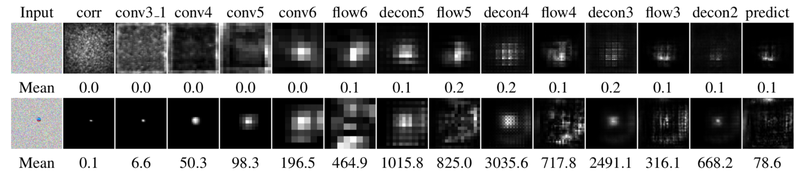

The key to making these systems robust is to look at the inner working of the system. Unfortunately, neural networks have millions of parameters, and it becomes impractical to look at how these parameters decide the response of the system. Therefore, we devised a Zero-Flow test. You see, if we supply two identical images, it should mean that there is no motion between them. Therefore, the optical flow system should produce zero motion. Moreover, we could reasonably say that the feature activations should also be zero. However, this is not the case. Even without a targeted attack, the optical flow systems produce some responses to identical images.

Network activations of FlowNetC on identical images with (bottom) and without (top) patch attack. Flow predictions and feature activations (top) are non-zero even without an attack.

We believe that this could be one of the main reasons why these optical flow networks are not robust to the attacks. Future research directions should focus on making the networks robust and examining them using the Zero-Flow test.

How to make self-driving safe?

It starts by making building blocks that are robust. Optical flow is one building block of a self-driving system, as is depth estimation, odometry estimation, and so on. We have a simple test that gives an insight into the robustness of optical flow networks. Such simple tests can also be designed for other regression problems like odometry. For instance, if the camera does not move, then the predicted odometry and corresponding feature activations should be zero.

However, it might be difficult to design these tests for adversarial attacks on high-level vision problems like image classification. Nevertheless, it would be easier to make the low-level problems like depth, optical flow and odometry adversarially robust. This could give insights into making problems like image classification more robust. Furthermore, we could also use consensus from the robust networks to detect attacks on the more vulnerable networks, like image classification and segmentation.

The road to safe-self-driving starts by understanding the vulnerabilities of the present day networks and fixing them for the future. This is the first insight into vulnerabilities of optical flow networks. We have, at least, some understanding of why the optical flow networks are vulnerable. It is time to fix them and move on to other systems which are critical for self-driving.

Further Information

For further information, check out the project page and the paper on arXiv.

Video:

The Perceiving Systems Department is a leading Computer Vision group in Germany.

We are part of the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Tübingen — the heart of Cyber Valley.

We use Machine Learning to train computers to recover human behavior in fine detail, including face and hand movement. We also recover the 3D structure of the world, its motion, and the objects in it to understand how humans interact with 3D scenes.

By capturing human motion, and modeling behavior, we contibute realistic avatars to Computer Graphics.

To have an impact beyond academia we develop applications in medicine and psychology, spin off companies, and license technology. We make most of our code and data available to the research community.